In his Gettysburg Address, President Abraham Lincoln used a score to measure a significant event:

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

A score equals 20 years.

On June 30, 2021, I will use score to announce a significant event in my life:

“Two score and ten years ago I retired from active duty in the United States Air Force.”

Everyone who wore a military uniform remembers special events that happened among comrades. Here are two of my memories:

A Shaky Command

My first assignment in the Air Force was as a medical corpsman at Lackland Air Force Base hospital. Schedules and timetables were always comfortable for me, so it was an easy adjustment to the specific times for patient treatments, appointments, precise timetables for dispensing medications, training, and housekeeping. At 1000 hours, I warmed the food cart, and at 1100 hours I took it to the mess hall to get enough food for 10 bedridden patients, including special diets. I was expected to return to Ward 18 at 1145 hours.

Ordinarily, the route from the mess hall required that I only negotiate one up-and-down ramp to cross the street that separated the wards and clinics. One day, work was being done on that single platform, thus forcing me to push the cart over a greater distance, and to negotiate two up-and-down raised areas that required more strength and critical timing. Even though I considered my 17-year-old body a neatly sculptured muscular machine, I also knew it was no match for an out-of-control food cart that doubled my 156 pounds. A lapse in timing or strength would put me and the patients’ chow in jeopardy. According to the Mess Sergeant, the food was more important than my body.

Although the first crossing was difficult, I computed the amount of energy and the angle of approach required for the second hurdle. Within thirty yards of the road, I checked for cars or anything that would impede my transition to the other side. The path was clear. Then, just as a pilot pushes the throttle to gain momentum, I started my thrust to give me enough speed to control my descent to the street and enough speed to carry me up the incline. My mechanics were good. It was a beautiful descent to the street, and I had generated more than enough energy to ascend, and according to my estimate I would turn the cart into the ward in 30-33 seconds. Then something else happened.

Suddenly, my eyes focused on a large contingent of very high-ranking military brass who suddenly emerged from the doorway adjacent to Ward 18, into the path of a fast-moving food cart under the precarious control of one PFC. All I could see was stars and eagles, (generals and full colonels). Even though one of them appeared to be younger than his colleagues, his uniform and hat was trimmed with gold braids, and his position in the group signaled preference and priority. I quickly assessed the situation. Stopping was an option that would have demanded more muscles than I could muster. Aiming for the wall to avoid a collision also seemed impractical. So, I very loudly issued the only shaky command that seemed appropriate. “Move it up front, I’m coming through.” These were military men and women who could distinguish between bravado, courage, and panic. They reacted to my panic and quickly widened the path. As I sped through the pack, the tall handsome man with four stars on his shoulder said softly, “It’s alright airman, go right ahead.” I simply said, “Sir”, as I made a sharp left turn into the ward and delivered lunch for my patients — on schedule. My supervisor, Sergeant Robinson, entered the kitchen, stared at me, and wiped his brow.

One of the nurses standing near the doorway whispered to another, “That’s him, the cute one.” She was describing General Hoyt Sanford Vandenberg, Air Force Chief of Staff

That night I wrote my mother, but I just couldn’t mention how I almost ran over the Air Force Chief of Staff with a food cart.

Later in my Air Force career I became a journalist and broadcaster.

There are many ways to express payback, or retribution. It is better to be the “payback-er” than the “payback-ee” One day the only word that seemed appropriate was —

Comeuppance

In March 1965, while serving as station manager of the Armed Forces Radio & Television station in Greenland, I was offered an unsolicited gift. My buddy, a supply sergeant, had recently been reassigned to Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, through which supplies for military bases in Greenland and Iceland were channeled. He called to offer me a new television transmitter that had just arrived for trans-shipment to another base in Iceland. I simply said, “Send it.” The transmitter arrived in Greenland. We installed it and put it to use that night.

Five years later I served as a senior instructor in radio and television at the Defense Information School, which trained military journalists and broadcasters. My supervisor was Navy Lieutenant Commander, Alice Bradford, a fellow Georgian. Unknowingly, we spent our childhoods less than 40 miles apart.

Our Program of Instruction in the Department of Radio/TV was changing, and each instructor had been assigned a portion to review and rewrite. My portion was finished. Then, Commander Bradford asked me to assume responsibility for another few more extensive chapters. When I reminded her that the extra load was burdensome, she asked me to accompany her to a soundproof radio booth. She had a smile on her face, which quickly turned to a giggle. With the door firmly closed, she calmly said, “Sucker, you stole my transmitter.” Of course, my memory temporarily failed me, but she provided the details. “Back in 1965, I was at the naval base in Iceland, waiting for a television transmitter that I had paid for. Somehow, it got diverted from Dover to you at Sondrestrom Air Base. It’s comeuppance time. You have no idea how long I’ve been waiting to get even.” Fortunately, we were in a soundproof booth, which hid our loud laughter and tears.

We emerged from the booth, wiping our eyes, just as the commandant approached. He simply looked at us and said, “Whatever it is, I don’t dare spoil your fun.”

At the end of the week, I delivered to Commander Bradford my completed assignment.

Good Memories

Good memories are treasures that we horde for ourselves.

Sometimes they are the only currency that can buy peace of mind.

They give us safe passage to where we were once content.

Good memories are not exhausted by time.

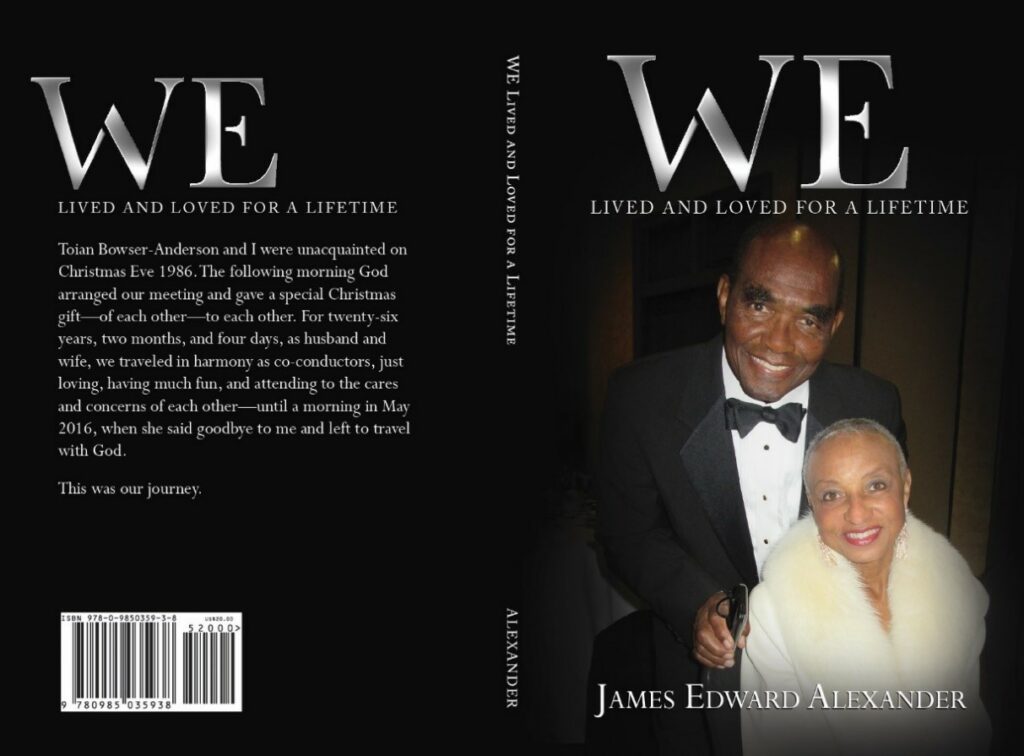

To order your copy of my latest book,

WE, go to www.jeatrilogy.com