Due to updates of my directory some of you are first time or restored recipients of the Story of the Month.

For all previous stories since May 2015, go to STORIES at www.jeatrilogy.com.

If you want to unsubscribe from these monthly offerings, please state your preference in a return email to jeatba79@gmail.com.

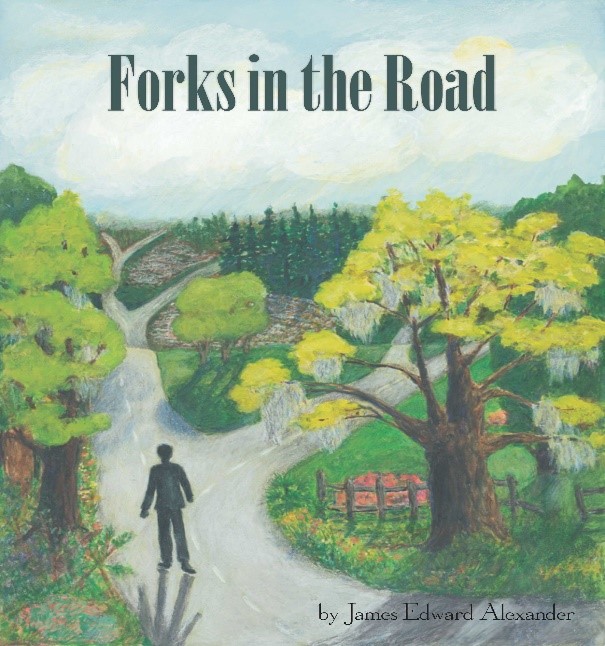

Continuing stories from Forks in the Road, that captured some memories of an exciting career in the United States Air Force, 1951 – 1971.

FIRST ASSIGNMENT, FIRST FRIENDS

On Sunday I spit-shined my shoes and pressed my uniform. Every man in my barrack had been through this ritual, and tomorrow was my day to be assigned my first job as a medic. Some even suggested places to work, as though I had a choice.

In 1951 the hospital at Lackland AFB was a wooden structure comprising three long corridors, which we called ramps that numbered A, B, and C, each stretching approximately one-half mile. Off of ramps A and B were entrances to surgical wards, surgery, and specialty clinics, each identified by a rectangular sign over the door.

My orders directed that I report to the Office of Surgical Services at 0700 hours Monday morning. At approximately 0645, I joined about 20 men and women with similar directives, including Chester Fowler, my colleague from basic training. At 0659 hours, a second lieutenant and two sergeants greeted us.

Our assembly followed the officer along Ramp A. As we approached WARD 18, a big muscular Colored staff sergeant waited in the door. His name tag read ROBINSON. He was the Ward Master, a title which recognized his proficiency as a medical technician, supervisor, trainer, and liaison between his subordinate medical attendants, doctors, nurses, and patients. He had been informed that help was coming. The lieutenant barked: Alexander, ward 18.

With the front and back doors open, Ward 18 also appeared to be a cavern with a total of 47 beds alternately lined on each side of an aisle. But upon entering I saw a window next to each bed and each patient had his own bedside stand for small personal belongings. Because the building was not air conditioned, an electric fan rested on each stand to rearrange the hot Texas air. In the middle of the ward a side door led to a screened porch. In addition, the front portion of the ward had been compartmentalized into a bathroom, kitchen, linen closet, utility room, nurses’ office, a treatment room, and two private rooms for patients with special problems.

Coincidentally, I arrived when most of the surgeons and senior nurses assembled to discuss each patient’s diagnosis, surgical procedure, and post-operative prognosis. Sergeant Robinson escorted me into their midst and interrupted: “Ladies and gentlemen, this is PFC Alexander, James E.” The leader of the group offered, “Welcome to the family, Private Alexander.” His name tag read GOLD, and he had eagles on his collar. He was Dr. (Colonel) David Gold, Chief of Surgery.

I was assigned to the day shift, 0700-1500, the busiest period for learning and applying new skills. In quick order, Sergeant Robinson, the nurses, and doctors introduced me to a vigorous on-the job-training (OJT) regime of fundamentals. They enjoyed teaching, and I enjoyed learning. All of the nurses and doctors were White. We all sensed something new; both teachers and student were in a new learning environment. In the third or fourth month a doctor entered the ward, asked Sergeant Robinson to excuse me for training elsewhere. The doctor led me to the surgery suite. He told me to take a seat in the corner and simply observe. A couple of hours later, as we walked back to the ward, the surgeon, a graduate of Rice University, made some comments; the most significant being: “Alexander, it takes a lot of hard work to do what you just observed. There’s something about you that tells me you can do it.” He had deliberately taken time and effort to offer advice and encouragement to a 17-year-old boy from Valdosta. The gesture continues to excite pleasant memories.

About three months later Sergeant Robinson told me to stay after work. We made our way to the back less-traveled ramp so that he could instruct me with fewer distractions. He reported that my appearance and quickness to learn and apply basic medical procedures was closely observed and applauded by the doctors and nurses, and “some special others.” That pleased him because it also projected his teaching skills. Then he offered his counsel, not as a supervisor, but as an older Colored brother preparing a younger sibling for a role in a society with strict rules for governing wide diversity of cultures, races, genders, and attitudes.

As we approached the end of the corridor, I saw other Colored non-commissioned officers waiting to greet us. Sergeant Robinson’s introduction: “Here he is.” Each of the three men wore enough stripes that signaled longevity in racially segregated units, before President Truman discontinued that separation three years earlier in 1948. These veterans had targeted me for grooming to manhood and honorable service in the “new world.” The senior among them was Master Sergeant Perry, whose service began in World War II as a Tuskegee Airman. He advised me: “Alexander, you’re off to a good start; keep your nose clean, and we’ll take care of you.”

Then Came Notices with Major Impact

In my seventh or eighth month as a medic, Sergeant Robinson smiled and he handed me a flyer that asked for volunteers to help the Red Cross escort patients to stock car races, football games, symphonies, rodeos, and other events, both on-base and in San Antonio. Two days later I was among the medical corpsmen and Red Cross staff who escorted approximately two dozen patients to a concert performed by the San Antonio Symphony Orchestra. Men in the orchestra wore tuxedos, and the women wore long black gowns, and they played violins, flutes, French horns, clarinets, English horns, harps – introducing me to new sounds and vocabularies. It was an impressive sight for a boy from Valdosta.

After a few more outings the Red Cross staff asked Sergeant Robinson to arrange my schedule so that I could be a regular assistant. He was pleased to accommodate, and he said to me, “You are the only Colored medic, and because you’re escorting military patients, you’re not segregated by race, as are the other Colored patrons. It’s a long hard road my young brother, travel well.”

August 1952 marked my first-year anniversary month as a medic. When I reported for duty on August 5th, I was notified that my friend and mentor was gone. Sergeant Robinson died last night, on August 4th, in a head-on collision of two Greyhound buses near Waco, Texas.

His words counseled me for the next two decades.

Good Memories

Good memories are treasures that we horde for ourselves.

Sometimes they are the only currency that can buy peace of mind.

They give us safe passage to where we were once content.

Good memories are not exhausted by time.

To order your copy of Forks in the Road

go to www.jeatrilogy.com