These two were originally presented in my second book, Forks in the Road, which shared memories of a career in the United States Air Force. They are repeated to show how my military service began, 70 years ago.

Open Wide — Everything

At precisely 5:00 a.m., June 22, 1951, the lights were turned on in the Armed Forces Induction Center in Columbus, Georgia, illuminating both the room and the path to my future. Those western movies depicting cattle drives pale in comparison to the pace with which we were herded through stalls for physical examinations. Our roundup began promptly after breakfast. Lines were formed, each comprising approximately 25 men.

We stood at the entrance to a large building, mindful of the sergeant’s plain directive: obey the medics and no talking, except to answer their questions. Doctors, nurses, and technicians opened the gates as other sergeants kept the stream of bodies flowing. Their technique was to literally strip everything and everybody to the bare bottom line.

I had been in a doctor’s office only three times in my life but was not required to undress during any visit. But these medics were trying to determine our fitness for military service, and they knew exactly what they needed to see and where to find it. We examinees moved to the rhythm of an incessant chorus of instructions: hold this straight, bend that, raise arms, lift feet, turn left, squat right, cough, and open wide – everything. One pair of hands checked the muscle tone of my neck and upper extremities, other fingers found my middle, front, and behind, leaving me befuddled. They used an assortment of gauges, scopes, mirrors, rubber hammers, scales, tubes, needles, bottles, and other instruments to get what they wanted. Everything they used was cold. It was an ignoble spectacle. But there was a war being fought in Korea, and the pipeline to the fronts needed a steady flow of bodies. No time to tarry.

As each man finished the examination, he was directed to another large room where he selected a seat next to another man who had just completed the common experience. Now we were a salt-and-pepper multitude, comprising a mixture of races, ethnicities, habits, and expectations that each man brought from towns and cities throughout Georgia, Florida, and Alabama. Eight others of my Colored friends from Valdosta enlisted with me, including Franklin Williams. When he finished the medical exam and took a seat, having to look past calm White faces to get his attention evoked strange emotions. He and I could feel a change coming.

A Pair of Aces

By the third day the most important change in our vocabulary was the way we cited the time of day. I didn’t yet know why, but military time is given in four numbers. So, instead of getting up at 4:30 a.m., we were roused out of our beds at 0430, and before the minute hand made a full circle, we had cleared linen from our bunks, eaten breakfast, and formed a ragged formation for the march to waiting buses.

Less than 12 hours earlier I raised my hand and took the oath of enlistment, promising, as I had done as a Boy Scout, to do my best. Almost three years after Executive Order 9981 was signed, we newly inducted Southern boys marched to the waiting troop train in separate racial formations. One sergeant commanded: “You White fellows fall in over here, you Colored boys fall in over yonder.” Another sergeant stood at the train entrance with his roster and clipboard and ordered each new recruit to board and yell his last name, first name, middle initial, and the newly assigned serial number.

“Alexander, James Edward, AF – – – – – – -,” I reported and stepped forward. That was my first violation of a military command. The sergeant told me so.

“Dammit boy, I didn’t ask for your whole horsepower (entire name). I said middle initial, what’s this James Edward crap?” Shaking, I responded, “But that’s what my mama named me – sir.” The U.S. Government had just given me a number with eight digits to wear around for the next four years and had just restricted the other five letters of my name which I carried for 17 years.

Our train waited on sidetracks to transport new airmen to Texas and a contingent of sailors and marines to Memphis and California. A slender Colored airman, a graduate of the all-Negro Ft. Valley State College, was charged with supervising the activities and conduct of Colored troops aboard the train. In the next coach he had a counterpart among the all-White riders. I remembered the stories of World War II soldiers and how they played cards and other games of chance while aboard troop trains and ships, so I called out and inquired if anyone remembered to bring a deck of cards. We were still within the city limits of Columbus when I got several affirmative answers, and seats were hastily rearranged to facilitate card playing. My card playing experience was limited to bid whist. Almost every Colored person I knew played bid whist. Poker was not my game, but I was willing to learn, so when another traveler suggested poker, we needed more players. I was psychologically ready to learn new things, and since poker was new to me, the facts were clear: No more than two of us were interested; we needed more players; somebody had to make contact next door, and since I was the one who wanted to learn, I also knew who would have to cross the platform that joined the racially segregated coaches. I found something to keep the door ajar so that “my side” could monitor my safety, and then crossed what was my Rubicon and came face-to-face with as many White airmen as there were Colored servicemen behind me.

Using the experience of playing quarterback, I assessed my situation, and in a matter of fact tone I announced, “We need two poker players.” More than a hundred eyes scanned my body. No one spoke. I broke the silence and said, “Look, I want to learn how to play poker, so which two of you want to help teach me?” A few of them rose from their seats. I had to quickly determine if they were advancing toward me as friend or foe, and if foe, how quickly should I get my little butt to a safer place. Then I spotted a short, skinny lad who appeared to be my age, and I said: “What about you, Assless, wanna play some poker?” A smile came to his face, and he said, “Assless, by God, I been called a lotta things, but never Assless.” There was laughter among the riders. Someone else blurted out to the young White boy, “Assless, damn if that Colored boy ain’t right. Where is your ass boy?” When the roar subsided, Assless answered me. “I ain’t too good at poker, but hell, it sounds like I know more ‘n’ you, so what the hell, let’s go.” Someone else shouted out, “I’ll play if y’all don’t play that draw crap. I play stud.”

At least 12 of us went to the rear. Both doors were now propped open, and after giving up their seats to make room for card games, some of the Colored airmen went forward and started another process — Colored boys and White boys getting to know each other. Assless said he’d teach me the game so that I could really learn, because, he added, “That stud playing jackass is my cousin, and I taught him to play. He don’t know jack shit. Besides, he cheats.”

Colored and White boys from Valdosta exchanged glances of recognition, and before long a strange new kind of segregation was taking place. White and Colored players from the same city played together, reinforcing the truth that color is the least important consideration when you’re among “your own kind.” Even though Assless was from Florida, he and I recognized something in common that signaled “our own kind.”

As our train headed toward Birmingham on that June morning the coaches seemed like rolling ovens. We opened the windows, and within 15 minutes the purpose of separating us by race was nullified. Everybody was black. Our seats were downwind from a billowing smokestack atop the coal burning engine. The filth was so immediate and permeating that one White observer said, “Well now, I’ll just pretend I’m Colored.” His former schoolmate jokingly told him, “The Colored folks sure as hell don’t want no White trash.”

These new relationships were moving to a new level characterized by lies, “trash talking,” and revelations for leaving home. A White boy from Daytona Beach, Florida, said he just wanted to kick somebody’s ass. The cops and a judge warned that if he kicked one more ass in Daytona Beach, they would shoot him in his ass. So, the judge decided that if he was going to kick somebody’s ass it might as well be a North Korean. We were put on a train and told when to get off, so we played cards and didn’t concern ourselves with time. Time passed like the deal.

In Birmingham we increased our load of servicemen and headed for Memphis. When someone felt sleepy, he napped where he sat. Assless snored, and while he slept, I became more adventurous and advanced to more of the front coaches. To my surprise, each coach was converted into a casino. Colored boys and White boys shot craps, played poker, and there was in progress one game of “Georgia skin,” a game my daddy warned me not to play. He predicted. “If you start at midnight, you’ll likely be broke and pee on yourself before dawn.”

We were on the outskirts of Memphis when a Colored marine taught me the rules of a new game called “tonk.” He was the biggest winner, so I reasoned that he must know something, if only how to cheat and not get caught.

My fortune was increasing as the train stopped. About ten minutes later we started moving again. Someone noticed that the coaches carrying the Air Force recruits had been disconnected, and that those of us now riding up front would make the trip to Camp Pendleton in California along a different route. I left my money on the table and raced to the exit and leapt from the slowly moving train and headed in the direction of the disjoined coaches. Fortunately, the passengers on the portion of the train that I was chasing could see my pursuit, and Ira Lee Carmichael and my new pal, Assless, rushed to the rear platform to encourage my progress. After I mustered a strong surge, they pulled me aboard. I collapsed. Less than a hundred yards further the train stopped again. It had reached the terminal — where it was headed for a three-hour layover. I had chased a train headed for the parking lot. Ira Lee, Assless, and I looked at each other. One of them said, “What do you say at a time like this?” My reply: “Don’t say anything ’cause I ain’t sure if I want to laugh or cry.” The three of us caught each other’s eyes again and did both.

Navy Shore Patrolmen (SP’s) came aboard and authorized us to disembark. My new buddy and I decided to stay together and find a place to buy a cold drink. The SP said we would have to go separate ways to find what we wanted. Assless spoke up. “We ain’t gonna bother nobody. All we want is a Coke.” The patrolman retorted with something about being bothered himself, particularly by what he called my buddy’s smart-ass attitude. Something other than common sense made us stand our ground. The cop softened. “Now listen, if I hear any ruckus from you two little farts, I’ll come on the double, kicking ass.” It was a good rest. Assless and I were inseparable during the rest of the trip.

Three days later we arrived in San Antonio, Texas. Sergeants and corporals in uniforms pressed and fitted for a good impression stood along the concrete platform to greet us. Our on-board supervisor said we were to remain seated until we received another briefing.

It was a short wait before a very tall blue-eyed sergeant stood in the doorway and commanded, “When you get off this train, you’ll form two columns and march over yonder to those buses. There will be no talking between the time I get through until you take your seat on a bus.” He paused for effect, then continued, “Now, y’all are gonna be instructed to do a lot of things. There’s three ways of doing them: the right way, the wrong way, and the Air Force way. You’re gonna do everything the Air Force way, and that means you’re to sound off loud and clear the answer to any question I ask, and your answer will be yes sir or no sir. Do I make myself clear?” He heard a few who said, “Yes Sir,” but it seemed to lack uniformity and volume. The sergeant shouted, “I can’t hear you.” “Yes Sir” was better the next time. He was pleased and further instructed, “Pick up your bags and follow me.” His words sounded familiar. Just then I remembered my grandfather, an African Methodist Episcopal Minister, quoting the command of Jesus Christ to the fishermen: “Pick up your nets and follow me.” The prospects for the fishermen were immediately better than those that awaited us.

The Sunday afternoon June Texas sunbathed us in perspiration, which streamed through three days of soot and grime. Finally, our convoy of blue buses halted in the middle of the thoroughfare near the main gate at Lackland Air Force Base. Several hundred recruits had arrived earlier and had formed rows, four deep, stretching at least three city blocks. It was an awesome sight.

Until three days ago when Assless and a few other White boys entered the Colored car, I had never been part of a racially integrated group of more than a dozen folks, and then we Colored participants were generally serving the Whites. Now I was among a mixed assembly of more than 2,000. There was a kind of nervous gaiety in the air. Quick conversations started among strangers, each person reaching out to offer, and hoping to receive, a gesture of understanding of the common state of apprehension. Suddenly, with promoting from none and a surprise to all, a daredevil broke the calm. Everything about the youngster was different. He wore western boots, a western hat, western shirt, jeans, and a heavy shoulder strap held his guitar firmly on his back. He just couldn’t resist a chance to play for the captive audience. All eyes turned forward to the position he assumed, which was not where he had been told to remain. He offered us an original western composition and was actually allowed to finish an entire verse before he was quietly circled by everyone who wore a stripe on his sleeve.

A brash little corporal, whose name tag read DUNCAN, approached the musician, extended his arms as a mother reaching for a newborn, and in a calm voice, ordered the troubadour to, “Give me that guitar, and if I see you move one inch from where I tell you to stand, I’ll remove these guitar strings and stick them, one-by-one, up you know where, followed by the rest of the instrument, which will be followed by my boot.”

When the final convoy of buses arrived, they joined the already assembled horde that came from urban centers, townships, barrios, farms, and ghettos. We represented almost every American community. There were graduates and dropouts of high schools, colleges, and seminaries. Some of them volunteered for military serial numbers rather than being assigned a prison ID. After the masses were formed into units of approximately 70 men, it became apparent that Assless and I would be separated. So, I asked Corporal Duncan for permission to say goodbye. He politely and quietly asked: “Now just tell me what you think would happen if every man here wanted to say goodbye to somebody else down yonder?” I answered, “Then they would have to ask.” He actually smiled and said, “You’ve got exactly three minutes.”

I left the formation and started searching, and when I spotted his little flat body, I headed through a line of men and was near my train partner when I heard the command, F-L-I-G-H-T, A-TEN-HUT.” Every man in his section stiffened. I had waited too late. He caught a glimpse of my face, and we both seemed disappointed. “R-I-G-H-T FACE.” They turned. “F-O-R-W-A-R-D, M-A-R-C-H.” They started to move. Their lines were unsteady and an unsteady airman near Assless swayed and veered a little, but a little space was all I needed to see all of him.

We had challenged some enduring Southern customs and mores. And, because of our common geography and social heritage, we also knew of relationships that transcend race, even in the ugliness of segregation. Now the Air Force would further reorder our lives. But for three days we were two special boys flaunting a kind of regional arrogance, and we enjoyed ourselves. He crossed the train door to enter a card game because he was cocky, brash, and confident. I stood there inviting integration from a potentially explosive platform because I was cocky, brash, and confident. We had passed each other’s first test. In Memphis we gave reasonable notice to a SP that the system would have to accommodate our new friendship. After all, we were now “men,” en route to preserve the American system, and we felt entitled to comment on how we wanted it to be.

Ironically, I don’t remember if we formally exchanged real names. I called him “Assless;” he called me “Podner.” Each of us responded to our greeting. We had spent our time together.

We never met again.

Good Memories

Good memories are treasures that we horde for ourselves.

Sometimes they are the only currency that can buy peace of mind.

They give us safe passage to where we were once content.

Good memories are not exhausted by time.

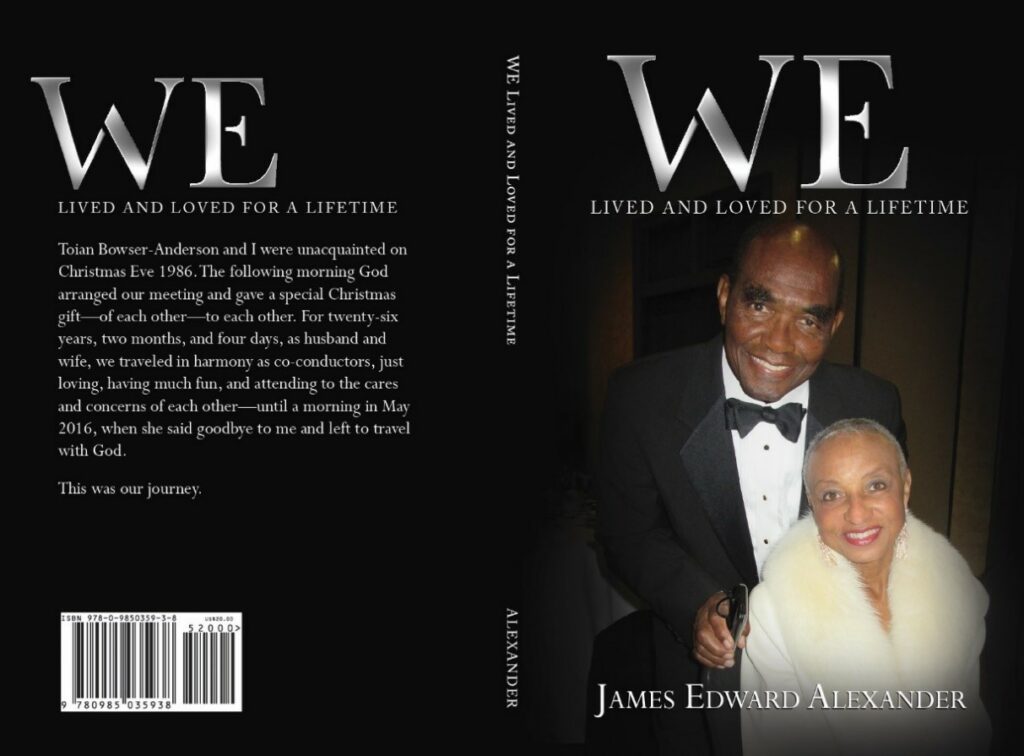

To order your copy of my latest book,

WE, go to www.jeatrilogy.com