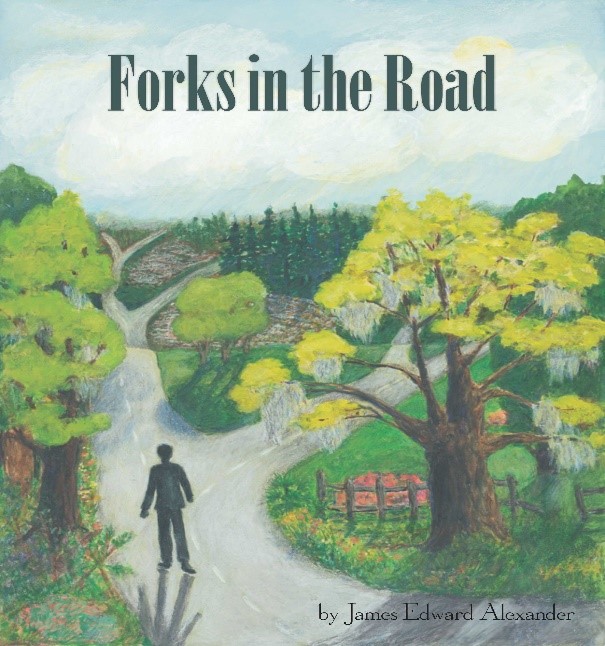

Continuing stories from Forks in the Road, that captured some memories of an exciting career in the United States Air Force, 1951 – 1971.

First Hear, Then Lead

Basic training was moving so fast that minutes, hours, and days seemed relevant only to those engaged in making us airmen. How and where they did it was according to timetables and procedures not of trainee making or approval. Whatever we did began when Sergeant Hall said FALL IN.

First Hear, Then Lead

Immediately after Flight 1607 was formed we began marching to other units which served our needs and augmented our training. At the Orderly Room each man received $40, and we marched to the Post Exchange (PX) to purchase toiletries, shoe polish, and other items for good grooming. From my position as Right Guide I also was first to enter the dispensary for shots and more medical exams and to the big open field for physical training. Within three days Sergeant Hall and Corporal Davis drilled us into a traveling unit where each man re-learned his left foot from his right. On the third night, Hall had to teach me a special lesson.

Our destination was the chapel. My attention was so attuned to doing a good job that I even began applauding myself. I was sure the men behind me looked as good as I did. As we approached the chapel, a flight of seasoned trainees was meeting us. I heard Sergeant Hall calling cadence, “Hup-two-hup-four, your-left-your-left-your left-right-left.” Suddenly, the cadence changed to, “Alexander, just where the hell do you think you’re going?”

His question was loud and clear, asked from where he and the rest of the flight had stopped — directly in front of the chapel — a few paces behind me. I hastily retreated, and heard Hall’s speculation: “Private Alexander, James Edward, no wonder you need three names – one for each head, because two of them must be up your you-know-where” He moved closer and was shouting into my left ear – on the head that was not “hidden.” Then he took off his hat; held it over my right ear, and commented, “You know what I’m doing?” It was a rhetorical question; privates don’t answer at a time like that. “I’m holding my hat over your other ear so that I can hear the echo of my voice, since I’m talking through a hollow canyon.” That stung. Fortunately, Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish chaplains waited to greet us. Drill sergeants don’t like to do their work in the presence of chaplains, because they often preface their commands with language the chaplains don’t find in their manuals. I was rescued by a chaplain who spoke up and reminded the sergeant that the orientation was scheduled to begin five minutes ago.

The next morning lights were to be on at 0500. Sergeant Hall stepped across the hallway to my room at 0445; knocked on the door and ordered, “Alexander, James Edward, get your ass up and take 15 minutes to wash out your ears. You can’t guide anybody if you can’t hear worth a damn.”

“I’m up sergeant, and yes sir, I’m gonna give my ears special attention.” I was indeed already awake. It had been a night of intermittent sleep. So much was on my mind. In all of my 17 years, I could never remember spending nights alone in my own room. Everything I did was at a pace to demand answers, even before I could ask the right questions. Who were those White men in church? What’s a Chaplain? What’s a Rabbi? Is that what White folks call their preachers? Back in Valdosta, Colored and White people were born, slept, dined, entertained, prayed, died, and were buried in separate places. Now, for the first time in my life, there was a White person within a few feet of me – every minute of every day. I had thoughts of what my mama would say if she could see me taking a shower. Until now, a #2 galvanized tin washtub or the big black wash pot in the yard was where I bathed – alone. Here, 73 Christian, Jewish, Catholic, Protestant bodies of varying pigments shuffled for a vigorous stream in the shower, using the same bar of soap to cleanse from our bodies the grime of basic training and, hopefully, to wash away years of accumulated racial and religious hatred, suspicious filth, and unfounded fear. My mind was restless. I was a long way from home.

On the fourth day of training, I asserted my leadership. Bill Craft was the right Squad Leader who marched immediately behind me. He claimed Kentucky as his home. Bill also had a good sense for maintaining a straight line, and constantly instructed: “Alexander, you’re guiding us straight for that parked car,” or “Alexander, steer your ass left, so that my right foot won’t be in the mud.”

On that day, I had heard enough of his instructions, and a fitting symbol of protest lay directly ahead. My concentration was intense as I maintained a straight course. At the right moment I took an unauthorized long step to avoid a pile of dog shit, but Bill didn’t have time to react. The pile was flattened by his right foot. Sergeant Hall saw what happened and knew why and how I did it. He tried to hide a smile. Bill promised that I would die slowly and painfully, but he later recanted and took credit for teaching me how to maintain a straight line, even if it led to a pile of dog shit.

A Taste of Freedom

For the first two weeks of training, we were restricted to the immediate area of our barrack. On the third Sunday we were ordered to dress in our best uniform and “fall in.” From my guide position I could see the chapel and was prepared, this time, to hear and to stop on command. But when we passed the steeple, I had no idea where we were headed, and if I didn’t know, everybody following me would learn the secret at the same time.

Finally, we arrived at Mitchell Hall, named in honor of General Billy Mitchell, a hero of World War II, who demonstrated the power of the airplane to sink ships. I entered through the front door into an auditorium bigger than the combined spaces of the three largest Colored churches in Valdosta, my only comparison. There was no balcony, as there was at the movie theaters in Valdosta, where Colored patrons sat. My eyes, conditioned by 17 years of racial separation, searched for a fellow Valdostan, or any Colored airman. Instead, it was a White airman from another flight who sat at my side. When he said “Howdy,” his Southern accent affirmed that both of us were learning new social skills.

Suddenly, there was an unusual sound of drums; starting slowly and softly and ending loudly, a level which I later learned to call a crescendo. Then a White man appeared and introduced the performers. During the next 45 minutes we watched jugglers, magicians, comics, and musicians. Before this day I had never seen a cello or violin, but I had seen some other instruments while standing on the curb watching the Valdosta High School band march in parades. We did not have a band at Dasher High School.

During the intermission, long lines formed for refreshments. I kept my seat; my thirst was for understanding as I pondered how much I had to learn. Soon, young civilian White girls served refreshments to those of us still seated. I couldn’t help wondering what my grandfather would say of this day. He once predicted that Colored folks would eventually move from serving to also being served, but we had to work our way to the front of the line.

Later that evening as I sat and shined shoes, I tried to understand how my life was changing. I had not yet learned new words like transition and perspective to help me understand. Self-teaching comes slowly, but that day I added the word crescendo to my expanding vocabulary. It was a good day.

Good Memories

Good memories are treasures that we horde for ourselves.

Sometimes they are the only currency that can buy peace of mind.

They give us safe passage to where we were once content.

Good memories are not exhausted by time.

To order your copy of Forks in the Road

go to www.jeatrilogy.com