Stories and memories of my grandmother always amuse, comfort, and give repeat lessons that still guide me. Sometime since May 2015 as I presented these monthly offerings, I have shared two of them. As I pondered which one I should repeat this month, the answer was simple – both.

The Shoe Box

Growing up in the 1930’s in Valdosta, Georgia, required the fast learning of two sets of rules and customs. Georgia, like all of the Southern states in that period, had separate laws and customs for Black folks and White folks. As a Black boy my parents taught that education was one way to overcome some of the harshness of segregation, but until I become wise enough to overcome, I should treat segregation as any problem that you can’t immediately solve: you must manage the problem to your advantage with whatever resources you have.

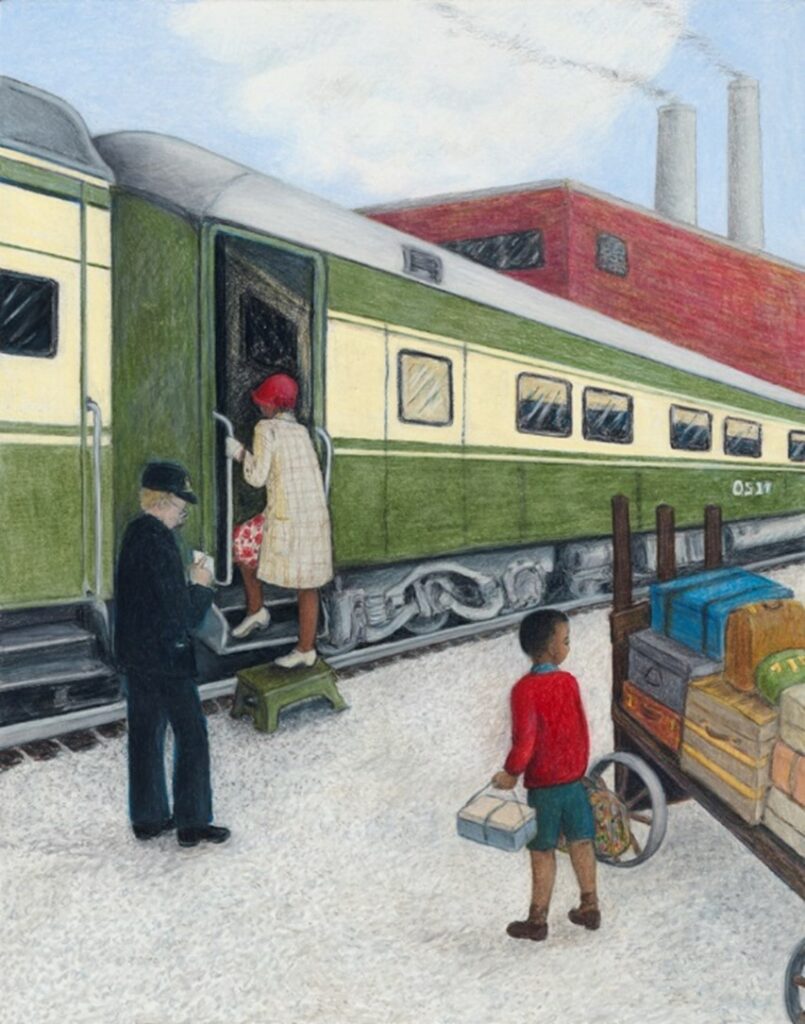

One community custom for “managing” a form of segregation was spawned in 1896. In that year the United States Supreme Court, in the case Plessy v. Ferguson, authorized Southern States to legally segregate public facilities for Black and White citizens, so long as they were “separate but equal.” The ruling specifically addressed separate railway coaches. Coaches for White passengers included dining cars. Black passengers had to pack their food. The most utile resource for that purpose was – a shoe box. There was a community understanding that whoever bought a new pair of shoes, the shoe box became community property for whoever needed it.

I was my grandmother’s travelling companion. A few days before our departure she carefully packed our clothes in her grip. When she told me our destination, it was my job to check the shed for a shoebox appropriate in size for the number of meals we needed. A shoe box for pumps or slippers would hold a sufficient meal for a trip to Atlanta, Macon, or Savannah. On our trip to New Orleans, we needed two large boxes. Two neighbors, who knew our requirement, delivered the boxes they saved when they bought new brogans. There also was an unstated requirement to prepare enough food to share with those who might not have a meal. Furthermore, there was a ritual and formality to what was packed and how it was presented.

The day before departure Mama carefully washed a special set of small porcelain bowls and a collapsible metal cup. She placed them near the hand washed and ironed napkins and lace doilies. Every time Mama washed a special set of utensils, she stroked them gently, and her gaze seemed far away. One day she told me why. Not too many years earlier those utensils were used for her feeding, in the hands of her grandmother, a former slave.

Immediately after we boarded the train, and before the coal burning engine jerked forward and sent a shockwave and a billow of black smoke back to our car, Mama lowered her head and talked to God. “Master, take us there and bring us home.”

The time to eat was when someone opened their box and the whiff of the staple, fried chicken, permeated the car. Within minutes the air was filled with the aromas of ham, catfish, hush puppies, butterbeans, cornbread, okra, squash, rutabaga and turnip greens, blackberry, and sweet potato pies. Foodstuffs that might melt or spill, like butter, gravy, and syrup, were packed and carefully wrapped in a container with a lid – a Prince Albert tobacco can. But even before travelers began their meal, someone, as though guided by another custom, would walk the aisle and offer grace. And quite often as we ate, someone would start humming a Negro spiritual, and all passengers joined in. It was a sign of unity. It also was a way to manage a problem, while working on a solution.

The “separate but equal” doctrine was overturned by another United States Supreme Court in the case, Brown v. Board of Education, 1954.

The Reach of Grandmama’s Hand

When I arrived at Westover Air Force Base in 1962, there was insufficient housing on base to accommodate me for four months of temporary duty at 8th Air Force Headquarters. I was given a voucher to pay for housing off base. Rather than stay in a motel, my inquiries about alternate accommodations eventually led me to the home of Mrs. Phillips in nearby Springfield, Massachusetts.

Mrs. Phillips and I exchanged greetings, while immediately making some assessments of things to help each of us determine our willingness to be either a landlord or a tenant: personal grooming, speech patterns, eye contact, type of automobile, wedding rings, and other “gut feelings” that either guide your hand to sign a lease to stay, or to grab your car keys to leave.

After our preliminaries satisfied each other to move to the next level, she led me upstairs to a duplex apartment. I was satisfied and ready to give her a deposit. She had more comments and questions that were presented in a tone I knew from childhood in Valdosta, Georgia, which also informed me how to answer. She said, “I see you’re a sergeant, so ya must be behaving. Where you from?” I announced that I was born and raised in Georgia. Mrs. Phillips gave me an intense look and softly repeated my name and my place of birth: “Your name is Alexander, and you’re from Georgia. Who are your people?” Mrs. Phillips’ question was the same that I had often heard my grandmama ask of new acquaintances. “Who are your people?” One day I asked grandmama the importance of that question. Without hesitation she said: “The answer sometimes helps me determine if I’m interested in further conversation or relationship, because I don’t want to know nobody who’s not somebody worthy of my time.” Then, she paused just long enough to allow me to appreciate her words, and she added: “Furthermore, I’m not interested in changing my standards.” My answer to Mrs. Phillips was crafted as though she and my grandmama shared values.

As I preceded her down the stairs I answered: “My mother’s maiden name was Catherine Alexander; my grandfather was Reverend George Alexander, and …” Suddenly, I felt a heavy hand on my shoulder, as she interrupted with another question in a loud voice: “Was your grandmama named Mariah?” She repeated the question, with emphasis: “Tell- me–if–your–grandmama’s– name-was– Mariah?” My body became rigid, and my tears quickly formed as I turned to answer a stranger who knew my grandmama’s name. She saw my face, and from the higher step behind me, she lifted my entire body and buried my head in her full bosom. My face was smothered, but my ears were partially uncovered, and as she clutched my suspended 170-pound body, I heard, “Your grandmamma saved my mama’s life, your grandmamma saved my mama’s life. Miss Mariah- saved- my -mama’s- life.” As she released me, I also saw her tears, and she uttered a sound that alerted me to prepare for another giant embrace. I took a deep breath and just hung on, as she danced us down the steps.

During the period of my grandfather’s ministry in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, he was assigned to churches throughout the State of Georgia. His most reliable ministerial assistant was my grandmother. Sometimes she assumed duties that were not commanded in either the Old or New Testament. One night a parishioner almost died during childbirth. My grandmother, acting as the midwife, completed the delivery and stemmed further crisis. The little girl who assisted my grandmother and knelt with her to comfort and pray for her mother was now sharing with me the history of that night.

Before she released me, Mrs. Phillips turned me to see her face and to hear her declare: “My apartment ain’t for rent to you. You’re the grandson of Miss Mariah. You just found your way home for as long as you can stay. Hallelujah!”

Good Memories

Good memories are treasures that we horde for ourselves.

Sometimes they are the only currency that can buy peace of mind.

They give us safe passage to where we were once content.

Good memories are not exhausted by time.